Pathophysiology of gastroenteritis

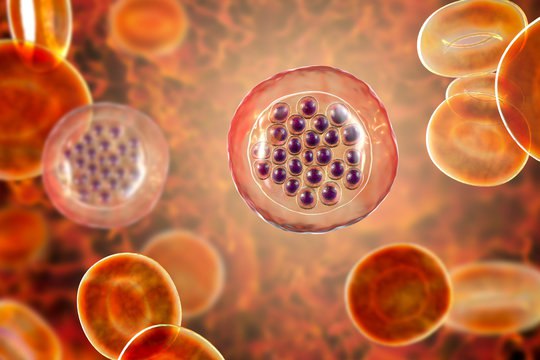

The GI tract is remarkably efficient at fluid reabsorption. Normally, of the 1 to 2 L of fluid ingested orally and the 7 L that enter the upper tract from saliva, gastric, pancreatic, and biliary sources, less than 200 mL of fluid are excreted daily in the feces. Thus, small increases in secretory rate or decreases in the absorptive rate can easily overwhelm the intestinal absorptive capacity. Diarrhea is generally defined as increased frequency (more than three bowel movements) or increased volume (>200 mL/day). Intestinal infection with bacteria, viruses, and

parasites that produce gastroenteritis usually follows fecal–oral transmission. Multiple host defenses are in place to protect the human GI tract. The principal defenses include gastric acidity and the physical barrier of the mucosa. A gastric pH less than 4.0 will kill more than 99% of ingested organisms, although rotavirus and protozoal cysts can survive. Patients with achlorhydria or hypochlorhydria from chronic atrophic gastritis, gastric surgery, human

immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, or proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use are at increased risk of developing infectious diarrhea. Disruption of the mucosal barrier, as with mucositis associated

with chemotherapy or irradiation, may predispose patients to gram-negative bacteremia. Increased peristalsis in gastroenteritis propels organisms along the GI tract, analogous to the cough reflex with clearing of the lungs. The intestinal flora forms an important element of the host defense, both in terms of quantity and composition. The small intestine and colon contain approximately 104 and 1011 organisms per mL, respectively. More than 99% of the colonic bacteria are anaerobes. Their production of fatty acids with an acidic pH and their competition for mucosal attachment sites prevent colonization by invading organisms. At the extremes of age, in children and the elderly, and after recent antibiotic use, the flora is altered and the risk for gastroenteritis may be increased in some individuals. Impairment of intestinal immunity is also a risk factor for intestinal infections.

Virulence factors play a complementary role in acute infectious diarrhea. Whether an individual

ingests an inoculum sufficient to establish clinical gastroenteritis is directly related to the organisms, community sanitation, and personal hygiene. Most organisms require an inoculum of 105 to 108 to establish infection. Exceptions include Shigella and protozoa such as Giardia, Cryptosporidium, and Entamoeba, which may cause diarrhea when only 10 to 100 organisms are ingested. Certain bacteria may produce toxins, which lead to a variety of clinical syndromes, and include enterotoxin (watery diarrhea), cytotoxin (dysentery), and neurotoxin. Botulinum toxin is the classic example of a preformed neurotoxin, but interestingly, both Staphylococcus aureus and

Bacillus cereus also produce neurotoxins, which act on the central nervous system to produce

emesis. Adherence and invasion factors facilitate colonization and contribute to virulence. Various forms of Escherichia coli express the gamut of virulence factors.